Iran’s Nuclear Dilemma: Snapback Sanctions and the Limits of Diplomacy

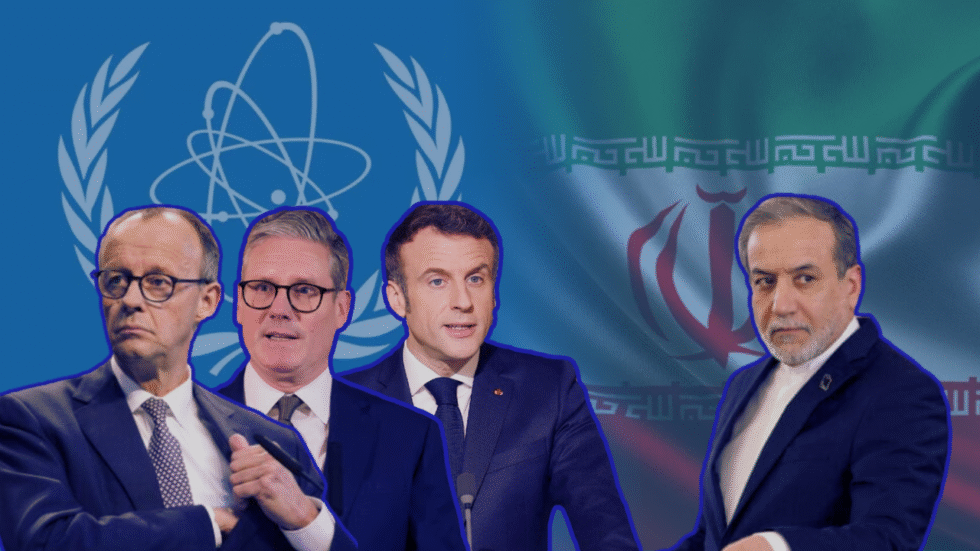

European powers have officially activated the snapback mechanism on Iran, after the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) failed to vote on the continuation of sanctions relief as part of the Joint Comprehensive Plan for Action (JCPOA).

Only Russia, China, Algeria, and Pakistan had voted in favor of the proposal, while the U.S., UK, Denmark, France, Greece, Panama, Sierra Leone, Slovenia, and Somalia had voted against.

Shortly after, Iran suspended all forms of cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Unless an extension deal is agreed upon, UN sanctions will take effect on September 27, 2025.

Understanding the implications of Iran’s position as a non-nuclear power requires an overview of past agreements between the state and international institutions, as well as an exploration of domestic divisions which continue to shape Iran’s nuclear policy.

The JCPOA’s Fragility

The JCPOA, also labeled the “Iran’s nuclear deal,” was an agreement formalized in January 2016 between Iran and the P5+1 (China, France, Russia, UK, U.S., and Germany), along with the European Union and IAEA oversight.

From the outset, the Obama administration positioned itself as the primary architect of the JCPOA, framing the deal as a landmark diplomatic achievement preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, while avoiding military conflict.

Washington’s approach combined sanction relief with ongoing oversight, portraying the agreement as a mutually beneficial compromise. Yet, even under Obama, the deal reflected broader U.S. strategic interests, ensuring Iran’s nuclear ambitions remained tightly constrained while maintaining American influence over the terms and enforcement of the agreement.

It was signed at a time when the centrist factions in Iran held the reins of power, but for the conservative factions, this deal contained a hidden reality that compromised Iranian sovereignty and deepened longstanding distrust towards the West.

Components of the deal included limiting uranium enrichment and stockpile, restructuring nuclear facilities, and granting expanded access to the IAEA for regular monitoring.

Eight years after the agreement took effect, also known as “Adoption Day,” all remaining EU nuclear-related sanctions and ballistic missiles restrictions were to be lifted on “Transition Day,” given positive conclusions from the IAEA. “Termination Day,” in 2025, would mark the conclusion of the UNSC’s consideration of the deal and the Iranian nuclear issue.

However, under Donald Trump, the U.S. had withdrawn from the JCPOA in May 2018, reimplementing sanctions.

The EU subsequently took the decision to maintain all restrictive measures on Iran even after the “Transition Day” planned for 2023. Thus, the JCPOA had served covert western interests, but failed to achieve its intended purposes for centrist and reformist factions in Iran.

The 12-day War: Attacks, Allegations, and Nuclear Tensions

After the IAEA levied accusations on Iran of non-compliance with the agreement, and its 2025 June report that Iran had acquired enough enriched uranium to produce nine nuclear warheads, Israel attacked Iran in the same month, with Benjamin Netanyahu citing Iran’s nuclear program as the basis for the preemptive attacks against military and nuclear sites in the country.

On June 21, 2025, the U.S. targeted three Iranian nuclear site locations—Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan—and claimed complete destruction, but several news agencies affirmed that the three sites had been abandoned and the equipment evacuated.

These attacks demonstrate the leverage held by the U.S. on the Iranian program, and the complicity of international institutions in the framework of modern warfare. U.S. aggression was justified on the basis of an Iranian threat proposed by the IAEA, despite the withdrawal of the U.S. from the nuclear deal in 2018 which would negate its legitimacy.

The Snapback Mechanism: Coercive Compliance

The snapback mechanism was integrated as part of the deal to facilitate an immediate response to any supposed Iranian violations.

Any report of non-compliance is to be met with the reimposition of sanctions after a formal UN process. On August 28, the foreign ministers of the E3 (France, Italy, and Germany) notified the UNSC of “significant non-performance” by Iran. They cited an increase in enriched uranium stockpile of more than 8400kg (over 40 times the agreed limit in the JCPOA).

The snapback would consequently revalidate UN resolutions prior to the JCPOA, including Resolution 1929, a clause that legitimizes military aggression against Iran as a “necessary measure” in the case of non-compliance:

“…Iran shall not undertake any activity related to ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons… States shall take all necessary measures to prevent the transfer of technology or technical assistance to Iran related to such activities.”

The Cairo Agreement: A Short-Lived Compromise between Iran and the IAEA

On September 9, 2025, Iran’s reformist Foreign Minister, Abbas Araghchi, signed an agreement with IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi in Cairo, Egypt, during European threats of snapback activation.

The agreement called for restarting nuclear inspections in Iran by the IAEA, after Tehran passed a law in July to end cooperation in light of the U.S. attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities. The diplomatic initiative was aimed at restoring Western approval of Iran’s nuclear activities.

Iranian perceptions of the IAEA and Rafael Grossi are predominantly negative, and this stance was publicly reflected during the 12-day war. Iranian lawmakers have accused the IAEA Director General of being a Mossad agent, referring to his biases in favor of Israeli policies in the region.

While the Iranian FM is greatly defensive of the IAEA-Iran deal, it has caused significant division among Iranian political and legal figures, as some consider it a violation to Iranian statehood, national security rights, and a sign of betrayal from pro-JCPOA politicians.

Following the E3’s snapback, Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) announced the suspension of all forms of cooperation with the IAEA and declared the Cairo agreement nullified. Nevertheless, this decision does not reflect comprehensive retaliation against Western sanctions, as it has merely brought the status quo back to the period prior to IAEA-Iran cooperation.

If tensions escalate, a total withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) could be back on the table, as Tehran has already directly threatened with such a proposition. Iranian media aligned with Leader of the Islamic Republic Sayyed Ali Khamenei, who has traditionally advised against nuclear negotiations with the West, have likewise thrown their weight behind this goal as well.

Reformists, Conservatives, and Nuclear Policy

The division between Iran’s political factions explains the intricacies behind disputes over interactions with the West. Simplifying these differences along the dichotomous line of ‘reformist vs. conservative’ is reductive, as the blocs represented by each title are not monolithic. However, these labels are important for distinguishing the positions on current developments.

Conservatives/principlists have prioritised clerical rule and a more isolationist stance towards the West. They dominate unelected bodies like the Guardian Council and seek to solidify the ideals of the Islamic Revolution.

Reformists tend to favor more cooperative and open relations with the West and a pragmatic approach to diplomacy. They seek to de-escalate tensions and build trust to alleviate the effects of sanctions. The current government is characterized by the election of reformist President Masoud Pezeshkian in 2024.

Conservative politicians in Iran have generally stood against the signing of the JCPOA, a move that reformists like Abbas Araghchi have commonly favored. While reformists perceive this policy as an improvement for Iran’s economic situation, conservatives see the JCPOA as a great threat to Iranian sovereignty. In 2015, an Iranian conservative lawmaker was recorded crying amid the signing of the nuclear deal.

As echoed by conservative factions, Western interventions in Iran’s nuclear program significantly strip the state of potential power acquisition. Iran’s position as the key leader in the Axis of Resistance against the U.S. and Israel—both nuclear powers—depends on its nuclear deterrence capability. The fatwa on the production and use of nuclear weapons issued by Leader Sayyed Ali Khamenei currently prohibits said activities for all political organisations. However, Islamic jurisdictions may be flexible when the survivability of a targeted entity is under threat:

“The Supreme Leader has explicitly said in his fatwa that nuclear weapons are against sharia law and the Islamic Republic sees them as religiously forbidden and does not pursue them…but a cornered cat may behave differently from when the cat is free and if [Western states] push Iran in that direction, then it’s no longer Iran’s fault.” Former Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi stated in an interview.

The conservative position considers deals like the JCPOA a direct threat to the survival of the Islamic Revolution. Unable to produce a weapon that would guarantee deterrence capability in the current balance of power, Iran would not be able to confront or resist Western hegemony.

Reformists have also failed to achieve specific objectives through their relatively open-handed approach to the West. Due to past developments like the failed “Transition Day” and the 2018 U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, sustainable sanction relief for Iran has not been consistent.

Playing Hardball: the Mechanics of Hard and Soft Power

Military-economic sanctions are a direct use of hard power by U.S.-European coalitions against the Islamic Republic. Sanctions have severely affected the structure of the Iranian economy. The reduction of oil exports drastically decreased government revenue, in which the oil and energy sector traditionally funded a large portion of the state budget.

As sanctions have limited the access to foreign currency, the value of the Iranian rial has plummeted into the world’s least valuable currency, driving down the population’s purchasing power.

After 2018, inflation skyrocketed to over 40%, and 27-50% of Iranians are currently living under the poverty line. Material consequences of such an exercise of power considerably debilitate Iran’s status in the international sphere, favoring its European and Zionist adversaries. Iran has been squeezed into an economically fragile space, compelling it to consider non-Western alliances with states like Russia and China.

Soft power plays by the West have also had significant consequences for the Islamic Republic. International campaigns against Iran have triggered internal and regional antagonism towards the state. The economic conditions manufactured by the West seek to pit the masses against the government, spreading wide dissent over the resistance ideology practiced by the Revolution, to rally the people for regime change.

Nonetheless, the Iranian population is not easily fractured. The nation has seen a great display of unity between individuals of various political positions during the 12-day war against Israel, demonstrating the recognition of a common enemy between the people: U.S.-backed Zionism.

On September 18, 2025, Iran withdrew a proposed UN resolution it had advanced with China and Russia that would prohibit attacks on nuclear facilities. The U.S., which ceased to be a member of the JCPOA, had been heavily lobbying behind the scenes to prevent the adoption of the resolution and threatened to decrease its funding to the IAEA if passed. Iranian politics is therefore not exempt from U.S. pressures, where their implications are reflected both on domestic and international arenas.

International Reactions and Strategic Calculations

The activation of the snapback mechanism was not a unanimous decision among JCPOA members. Both China and Russia considered the decision as illegal and invalid, suggesting that business with Iran will continue between the countries as usual.

China claims that Iran is not seeking nuclear weapons, and that its nuclear program is peaceful—a position it has maintained throughout the entire period in which the JCPOA was active. Unilateral actions, as echoed by China, undermine multilateral diplomacy.

It is essential to understand the complexity of dynamics behind Iran’s status as a non-nuclear power in the international system. Far from a single voice, Iran’s foreign policy has been influenced by internal divisions, Western impositions, Islamic jurisdictions, and international alliances.

These intersecting forces reveal not only the extent of Western coercion designed to shape the country’s nuclear trajectory, but the ongoing drive to keep Iran’s sovereignty intact.

If you value our journalism…

TMJ News is committed to remaining an independent, reader-funded news platform. A small donation from our valuable readers like you keeps us running so that we can keep our reporting open to all! We’ve launched a fundraising campaign to raise the $10,000 we need to meet our publishing costs this year, and it’d mean the world to us if you’d make a monthly or one-time donation to help. If you value what we publish and agree that our world needs alternative voices like ours in the media, please give what you can today.