The Profits of Perpetual Crises: How Western Hegemony Thrives on Global Conflicts

For decades, Western hegemonic powers have operated within a global order where conflict is not merely an unfortunate byproduct of geopolitical competition, but a structural instrument of power. Wars, sanctions, political crises, coups, and humanitarian disasters have become levers for influence, market control, resource access, and strategic dominance. The persistence of conflict in the Global South is rarely accidental and almost never divorced from wider systems of power that benefit from instability.

The wars in Sudan, the economic strangulation of Venezuela, and the unending devastation in Gaza may seem like unrelated crises, yet they are connected by a deeper architecture: one in which Western states and corporations maintain dominance not through overt colonial rule but through manipulation, exploitation, or strategic management of chaos.

Sudan: A Fragmented Nation at a Strategic Crossroads

Since April of 2023, Sudan has been facing what can be referred to as the most dangerous crisis since its independence in the 1980s. With numerous coups, internal tensions, reaching the war that led to the secession of South Sudan, Sudan is a nation that has not known tranquility, and especially across the period spanning about 3 years now.

The ongoing conflict in Sudan between the Sudanese Army, led by Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), led by Mohammad Hamdan Daglo, known as Hemedti, is due to a combination of historical, political, and economic factors, orchestrated, exacerbated, and exploited by external parties.

With its rich historical legacy and vast natural resources, coupled with a strategic geographical location, Sudan holds a place of considerable weight and importance.

Traces of the earliest human settlement in the Nile Valley and Sudan have been found; the Kingdom of Kush, one of the greatest kingdoms of ancient Africa on all levels, was established there; the kingdom which even ruled Egypt itself at one point in history. Christian kingdoms arose and maintained a remarkable model of spiritual and cultural prosperity for centuries, before the waves of Islamic and Arab conquest reached Sudan, weaving a new identity out of the blending of Arab, African, Islamic, Christian, and ancient local religions.

However, the modern state and harsh external interventions in Sudan did not allow for the protection of this diversity but rather turned it into a field of conflict and internal crises, while external interventions created permanent crises and conflict in Sudan.

When Omar al-Bashir seized power through a coup in 1989, Sudan entered a prolonged era of repressive security rule. The military and intelligence services dominated the state, governing in alliance with Islamist movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood. It was under this system that Darfur—an ethnically diverse region—became the site of one of Sudan’s greatest tragedies.

As segments of Darfur’s non-Arab population rose up in rebellion, the government responded by arming Arab tribal militias that later became known as the Janjaweed—the same militias that eventually evolved into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under the leadership of Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, “Hemedti.”

Over the three decades of al-Bashir’s rule, Sudan witnessed the secession of South Sudan and the devastating war in Darfur, culminating in a popular uprising that toppled him in 2019. These thirty years were also marked by severe U.S. economic sanctions and international legal proceedings against al-Bashir himself for war crimes in Darfur. The economy steadily deteriorated, corruption spread through state institutions, and the regime’s alliances shifted dramatically.

In the early years, Bashir positioned Sudan as a staunch supporter of anti-Israeli forces in the region—particularly in Palestine—and maintained close ties with Iran. Yet in the final five years of his rule, he pivoted sharply, cutting relations with Iran and regional resistance movements and moving instead toward Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and the United States. Both the Sudanese army and the RSF joined the Saudi-Emirati military campaign in Yemen beginning in 2015. In its last phase, the Bashir government even began signaling openness to establishing relations with the Israeli entity.

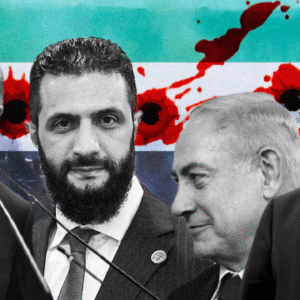

Following Bashir’s ouster, a civil–military transitional partnership took shape. This period saw an unusual political consensus that ultimately brought Sudan into the regional bloc of regimes normalizing ties with Israel. In February 2020, army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan met with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Entebbe, Uganda, in a meeting brokered by the United States and the UAE. The transitional authorities justified this move by citing the urgent need to escape crippling U.S. sanctions.

Yet less than two years after the normalization process began, power struggles between the civilian and military components of the government erupted, leading to the collapse of the transitional period in October 2021, paving the way for the war that followed. The Army Chief and RSF leader turning against their civilian partners did not mean the explosion between the two men’s armies was not inevitable.

With the Sudanese state collapsing into war-driven chaos, only two forces remain capable of defining frontlines and territorial boundaries: the army and the parallel militia seeking control over the entire country. This is simply because Sudan no longer has functioning institutions able to regulate or guide events. There is no national authority with real decision-making power.

The army—regarded as the legitimate heir of the Sudanese state and the bearer of its historical prestige—views the current battle as a fight to prevent the country from disintegrating. The RSF, by contrast, emerged from the fringes of earlier conflicts, grew through the war economy, and has transformed into an equally ambitious and capable rival force. It is now attempting to forge a new form of legitimacy through force rather than through constitutional means. After 2023, the Janjaweed-origin RSF faced widespread accusations of genocide and ethnic cleansing against non-Arab communities in the region.

From its inception, the RSF’s leader, Hemedti, succeeded in building a formidable military force that played a significant role in regional conflicts, including the aggression on Yemen and the war in Libya. Hemedti has also been accused of controlling several Sudanese gold mines and of smuggling gold to the United Arab Emirates. Meanwhile, the Sudanese military alleges that the UAE provides direct support to the RSF, including drones used to strike targets across Sudan.

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have achieved a significant strategic advance by seizing large swathes of territory along Sudan’s borders with Libya and Egypt. Following their capture of El Fasher in late October 2025, the RSF emerged as the dominant power across most of Darfur and extensive areas of neighboring Kordofan. Their July 2025 announcement of a parallel government heightened fears that Sudan could descend into a new fragmentation, reminiscent of the secession of South Sudan in 2011, which had taken with it the majority of the country’s oil reserves.

Meanwhile, the Sudanese army retains control over much of northern and eastern Sudan, including the Red Sea region, relying heavily on clear support from Egypt due to longstanding geopolitical ties, particularly concerning their shared border and the Nile River. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan relocated his political and military headquarters to Port Sudan, which now serves as the seat of the internationally recognized government, though security within the city itself remains fragile.

It is evident that Sudan is mired in a profound internal crisis. However, it is also crucial to highlight that foreign powers interfering in Sudan—such as the United States and the UAE—do not act in the nation’s best interests, pursuing their own agendas instead.

The political position of the Sudanese state qualifies it to be influential in the region. For instance, before 2015, when Sudan supported anti-Israeli forces in Palestine, its role was far from marginal. Khartoum acted as both a conduit and source of weapons to the Gaza Strip, whether through local manufacturing or imports from Iran, and served as an incubator for various forces confronting Israel. This history explains why certain countries and actors aim to control Sudan, turning it into a proxy for regional ambitions.

Geographically, Sudan occupies a pivotal position: it borders Egypt, Libya, Chad, the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and South Sudan. Its coastline along the Red Sea adds strategic importance, as it represents a major lifeline for global trade. Coupled with this, Sudan’s enormous natural wealth makes it a prime target for regional and international ambitions, with gold being the most significant prize. Sudan is among Africa’s largest gold producers, with official production exceeding 64 tons. However, smuggling is widespread, with reports suggesting the majority of Sudanese gold is smuggled to the UAE.

Sudan’s wealth extends beyond gold. Its mineral resources—uranium, chromium, iron, and copper—remain largely untapped. Its agricultural potential is immense: over 60% of the country is suitable for farming, nourished by the Nile and other waterways. Sudan produces roughly 80% of the world’s Arabic gum, as well as sesame and cotton. This abundance has attracted interest from Gulf countries for decades, as many struggle with scarce arable land, while American multinational corporations also seek to secure fertile territory.

Livestock is another key resource: Sudan is home to more than 100 million heads of cattle, making it one of the largest livestock producers in the Arab world and Africa. Petroleum remains important as well, since although Sudan lost most of its oil wells after South Sudan’s secession, the transportation lines and export facilities remain within its borders. Additionally, Sudan has excellent potential for solar energy production. Its strategic access to the Red Sea via Port Sudan also positions it as a critical trade gateway for landlocked African nations.

These factors collectively explain why countries such as Egypt, the UAE, and the United States are intensely interested in Sudan, even aspiring to achieve full hegemony over the nation.

This is to say that while the war in Sudan has clear internal roots, it would be an oversimplification to reduce it solely to a power struggle between Hemedti and Burhan, or even to frame it merely as a dispute over gold mines, which was indeed one of the triggers of their conflict. The war is not fundamentally a human rights issue either. Both parties have been implicated in past crimes in Sudan and were active partners in supporting Saudi and Emirati operations in Yemen.

The issue also goes beyond the ambitions of certain regional powers, such as the UAE, to prevent a pro–Muslim Brotherhood government in Sudan. Egypt’s position is also crucial: despite its strong opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood, it backs the Sudanese military—an institution that its opponents accuse of having ties to, or being influenced by, the Brotherhood. Each of these dynamics could alone provoke conflict.

However, the root of the current crisis lies in the struggle for hegemony over Sudan. From the outset, the conflict was never merely a clash between two military leaders. As noted by the United Nations and international research centers, it rapidly evolved into a proxy war, with the interests of regional and global powers playing out across Khartoum, Darfur, and Port Sudan.

Sudan is one of Africa’s gateways to the world. It offers access to the Red Sea and possesses vast natural wealth. What is unfolding in Sudan is reshaping the balance of power across the Horn of Africa, the Levant, and North Africa.

The conflict in Sudan—and the competition over Sudan—is a struggle for control of the Red Sea, the Nile River, subsoil resources, and the future of the entire region. Regional and international support for both the RSF and the Sudanese army is the decisive factor that prolongs the war and complicates any political solution.

Regarding the United States and Israel, the war in Sudan is viewed as a strategic pivot in the contest for regional and global influence. Washington is determined to prevent Moscow or Tehran from gaining a foothold on the Red Sea, but even more critically, it seeks to prevent Sudan from acting as an independent actor capable of making regional political decisions aligned with the will of its people. Israel, for its part, is focused on controlling shipping routes while keeping Sudan weak and subordinated.

Israel’s role in Sudan is both undeclared and influential. Viewing Sudan as central to regional balances and broader conflicts, Israel has intensified ties with Khartoum since Sudan joined the Abraham Accords in 2020. In return, Khartoum froze Hamas’ assets in Sudan.

Israel maintains connections with both sides: the Foreign Ministry leans toward Burhan’s army, while Mossad has cultivated close ties with Hemedti and the RSF through the UAE, particularly after Hemedti deepened his collaboration with the UAE during the Yemen conflict. However, these alliances mean nothing as both the Foreign Ministry and Mossad aim to serve the same purpose.

Finally, the United States holds the most significant influence over the Sudanese conflict. Washington maintains strong ties with both sides and possesses the capacity to halt the war by pressuring its allies to cease support. However, current indications suggest that the U.S. strategy is to allow the conflict to continue until both parties are weakened enough to request Washington’s intervention. At that point, the U.S. can impose its terms, with expected objectives including dominance over Sudan’s wealth through American companies and full control over the country’s political and military decision-making.

Venezuela: Oil, Sanctions, and the Politics of Destabilization

The United States’ threats to escalate hostilities against Venezuela did not emerge spontaneously. In July 2025, Venezuela held municipal elections in which the United Socialist Party won 285 out of 335 municipalities. These followed legislative elections in May, where President Nicolás Maduro’s coalition secured 253 out of 285 seats.

In both elections, Venezuela’s internal opposition boycotted the process, viewing Maduro—re-elected in 2024 despite immense economic and political pressure—as illegitimate. The opposition, supported externally by the U.S., refused to recognize any decisions by the Venezuelan authorities. The United States, dissatisfied with Maduro’s re-election and the results of the legislative and municipal elections, decided to disregard the will of the Venezuelan people and escalate its campaign to overthrow the government.

In August 2025, the U.S. Department of State announced a $50 million reward for information leading to Maduro’s arrest, framing him—an internationally recognized head of state—as a fugitive allegedly involved in drug trafficking to the U.S.

Since the 1950s, Washington has sought to control Venezuela, and in recent months, this pressure intensified under the pretext of combating drug trafficking; the White House accused the Venezuelan government of operating as a terrorist drug cartel led by Maduro.

Following the reward announcement, U.S. President Donald Trump ordered the deployment of over 10 warships off Venezuela’s coast, along with a missile cruiser and a destroyer in the Pacific Ocean south of Panama. These vessels are equipped with Tomahawk cruise missiles capable of striking targets within Venezuela. Additionally, the U.S. stationed F-35 fighter jets in Puerto Rico.

In response, Venezuela deployed warships within its territorial waters and mobilized 15,000 security personnel along its border with Colombia under anti-drug trafficking operations.

Here lies a lesson in the nature of colonial powers: Venezuela poses no offensive or defensive threat to any country, including the United States, has no expansionist ambitions, and has engaged in negotiations to lift sanctions. Yet, it now faces the risk of external military invasion and internal chaos that could lead to civil war or regime change. U.S. conduct toward Venezuela demonstrates that a nation does not need weapons, a nuclear program, or any resistance movement to provoke U.S. intervention. Simply refusing to serve American interests can trigger attempts at colonization, occupation, or coercion. In such cases, diplomacy is ineffective, and international institutions, dependent on U.S. influence, provide no real protection.

For example, Venezuela’s ambassador to the United Nations, Samuel Moncada, appealed to Secretary-General António Guterres to intervene, urging the U.S. to cease hostile actions and respect Venezuela’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence. The response? Nothing. U.S. threats continue to escalate, while the UN remains powerless to prevent an attack on a nation that poses no threat to its security.

Pino Arlacchi, former Deputy Secretary-General of the United Nations and former Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), published an article recounting his time leading the UNODC. He wrote, “I never had visited that country because Venezuela has always been outside the major cocaine trafficking networks between Colombia, the main producer, and the United States, the main consumer.” The UN Office on Drugs and Crime deemed it unnecessary to visit Venezuela, as the country’s narcotics-related file did not merit research or action.

Arlacchi’s words directly contradict U.S. accusations that Venezuela serves as a conduit or source of narcotics entering the United States. According to the UN official, these claims are false: Venezuela is neither a conduit nor a source, nor is it classified as a major drug trafficking country. He further emphasized that the Venezuelan Bolivarian Socialist Government’s cooperation in combating drug trafficking is among the best in South America. By this account, Venezuela and Cuba—Latin American countries often targeted by U.S. allegations of terrorism and drug trafficking, and subjected to harsh sanctions under these pretexts—actually maintain some of the strongest records in the region in the fight against narcotics.

The actions and threats of the U.S. in Latin America, and specifically in Venezuela are a form of contemporary Western colonialism. The interests of the masses, and slogans of democracy, freedom, development, justice, fighting crime, combating terrorism, and more are all simply pretexts they invent to occupy countries, control their fates and that of their peoples, and dominate their resources and wealth.

The motives behind U.S. aggression being centered on one country more than another boils down to the natural resources that are of interest to the United States, as well as being situated in a location that is of interest to it. Sometimes it doesn’t even need to be located in a geographically strategic location. It just needs to possess natural resources for the United States to wish to dominate the country, and which is what determines the level of U.S. aggression towards a country.

Why does the world not hear of an anti-drug trafficking campaign against Ecuador, when in 2024, European authorities seized 13 tons of cocaine on a ship arriving from there? The answer lies in geopolitics. Ecuador barely produces 0.5 percent of the world’s oil as of 2022, and the Ecuadorian government does not challenge the hegemonic policies of the United States in Latin America. In fact, the Ecuadorian regime is part of the U.S. hegemonic system in Latin America.

Venezuela, on the other hand, holds a key resource that is central to US greed: oil.

The United States’ appetite for Venezuela’s oil was stated clearly by Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, who considers the U.S. escalation as the biggest threat the continent has seen in the last 100 years. Maduro believes that the US, under the pretext of combating drugs, seeks first to get its hands on Venezuelan oil and gas.

Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world, grown in recent years due to new extraction techniques. Venezuela has the world’s fourth-largest gas reserves, with reserves scattered throughout the Caribbean, specifically where the US has sent its warship fleet. In addition to oil and gas, according to Maduro, Venezuela has one of the largest gold reserves in the world. Moreover, there are about 30 million hectares of arable land. It has abundant water resources and is situated in a geographical location which links Central America, South America and the Atlantic Ocean.

U.S. forces in the Caribbean have attacked boats, claiming they were loaded with drugs, killing 61 people since early September. The victims were labeled as drug terrorists by the U.S., while Venezuelan authorities described it as an execution. And although Venezuela has the right to respond in defense of the lives of its citizens and the unjustified attack on them, it practiced restraint, not providing the U.S. with the pretext to carry out its planned military operation.

The executions carried out by the U.S. military on Trump’s orders in the Caribbean Sea have provoked a reaction even by some U.S. media which usually provides cover to all the crimes committed by the US government. For example, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. administration officials said that Trump is enacting his constitutional authority as commander-in-chief. This means that when the U.S. military ordered the destruction of a ship in the Caribbean, officials considered the drugs the ship was allegedly smuggling to be an imminent threat to US national security. But, according to the Wall Street Journal, this claim was sharply rejected by legal experts and a number of U.S. lawmakers, who said that Trump is exceeding his legal authority to use lethal military force against a target that does not pose an immediate threat to the United States, and that Trump is required to seek congressional authorization.

Since 2015, the US has increased its economic sanctions targeting the oil sector, the main source of funding for public expenditures in Venezuela. The sanctions peaked in 2019 in parallel with the United States’ support for opposition leader Juan Guaidó, who declared himself interim president of Venezuela. Contrary to any democratic principles, the U.S. along with European and some Latin American countries recognized Guaidó and severed ties with the legitimate and elected government of Caracas led by Nicolás Maduro.

In the same period, Venezuela witnessed a large number of military and security sabotage attempts, a military coup attempt, as well as sabotage operations targeting the energy sector, electricity, in particular. These attempts were run by the CIA, according to Sergio Guzmán, director of Colombia Risk Analysis.

But after the outbreak of the Ukrainian-Russian war, and fearing a rise in oil prices, Washington took the initiative to request informal talks with Venezuela. Washington wanted Venezuelan oil to flow and maintain a low global price for oil. In return, it promised to lift sanctions on Venezuela. But in 2024, the talks reached an impasse when Maduro was re-elected and Donald Trump came to power again in Washington.

A World Order Sustained by Instability

Protracted conflicts rarely exist in isolation; they are often sustained by the strategic interests of hegemonic powers. The Western-led international system does not inherently require peace; on the contrary, instability frequently serves its architecture of global dominance, where every local crisis generates clear advantages for external actors. Weakened states make resources more accessible, whether gold in Sudan, oil in Venezuela, or the occupation of Palestine. Instability justifies militarization.

Economic collapse and humanitarian aid become tools to increase dependency and influence, while rival powers of Western colonialism are contained. In every case, these conflicts reinforce geopolitical hierarchies, illustrating a grim reality: as long as instability serves strategic, economic, and political goals, external powers have every reason to not only allow it to persist, but to orchestrate, enable, and sustain it.

If you value our journalism…

TMJ News is committed to remaining an independent, reader-funded news platform. A small donation from our valuable readers like you keeps us running so that we can keep our reporting open to all! We’ve launched a fundraising campaign to raise the $10,000 we need to meet our publishing costs this year, and it’d mean the world to us if you’d make a monthly or one-time donation to help. If you value what we publish and agree that our world needs alternative voices like ours in the media, please give what you can today.