Today in History: the CIA-MI6 Coup that Overthrew Iran’s Prime Minister

“My greatest sin is that I nationalized Iran’s oil industry and discarded the system of political and economic exploitation by the world’s greatest empire. This came at the cost of myself and my family, and at the risk of losing my life, my honor, and my property. I am well aware that my fate must serve as an example for the future of the Middle East in breaking the chains of slavery and servitude to colonial interests.”

— Mohammad Mossadegh, during his trial in a military court on Dec. 19, 1953.

The Crime of Sovereignty

On the morning of Aug. 19, 1953, Tehran awoke to a city transformed by deception, chaos, and covert power. Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh, the man who had dared to reclaim Iran’s oil and assert its sovereignty, was toppled—not by his own people, but by a carefully engineered alliance of foreign intelligence and political manipulation.

The CIA and Britain’s MI6 staged a coup dressed in the rhetoric of anti-communism, concealing the true aim: to seize control of Iran’s wealth, reshape its politics, and preserve imperial dominance. What unfolded was a relentless campaign of influence and intimidation, striking at a nation’s independence while forging a resilience no foreign hand could extinguish.

Mossadegh’s nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) was an act of reclamation: Iran asserting control over its resources and shaping its own course after decades of foreign exploitation. In response, Western powers reframed this as a threat—to British prestige, to U.S. strategic calculations, and to a global order defined by their interests.

What Mossadegh faced was not just opposition; it was an empire mobilized to punish independence.

The significance of 1953 extends far beyond Iran. It established a model for intervention that would repeat across continents and decades: elected leaders removed, economies sabotaged, and democracies subverted in the name of stability, freedom, or anti-communism.

From Guatemala to Chile, from the Congo to Indonesia, Mossadegh’s overthrow became the template of covert imperial action—a lesson in the fragility of sovereignty under the shadow of foreign power.

This account revisits the Abadan Crisis, the assertion of Iranian independence, the mechanics of Operation AJAX, and the enduring legacy of a leader whose tenacity continues to resonate.

It is a story of betrayal, resilience, and the relentless struggle for national self-determination—a struggle Iran continues to bear seventy-two years later, marked by both loss and the persistence of its resolve.

Historical Context & Lead-Up

Mohammad Mossadegh was born on June 16, 1882, into a prominent family in Tehran. His father, Mirza Hedayat Ashtiani, served as Iran’s Minister of Finance, and his mother, Najm al-Saltaneh, was closely related to the Qajar dynasty.

After his father’s death from cholera when Mossadegh was just 10, his mother instilled in him a profound sense of public service:

“A person’s worth in society is dependent on how much one endures for the sake of the people,” she told him, words that Mossadegh later said prepared him for a life of political struggle and personal sacrifice.

He received a rigorous education in Iran and abroad, studying law in France and later earning a doctorate from the University of Neuchatel in Switzerland. Despite chronic health issues, he built a career as a lawyer, parliamentarian, and minister, cultivating a reputation for integrity, nationalist conviction, and deep commitment to constitutional governance.

By the late 1940s, Mossadegh had emerged as a leading voice against foreign domination and corruption, advocating for the sovereignty of Iran’s resources and the principles of parliamentary democracy. His moral authority and nationalist credentials positioned him as the figure capable of challenging entrenched colonial interests.

By 1951, Mossadegh ascended to the premiership following widespread popular support and parliamentary victories by the National Front. One of his first and most consequential acts was the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, which had long exploited Iran’s oil under extremely favorable terms for Britain, leaving Iranians with minimal benefit.

At the center of the dispute was Abadan, home to what was then the world’s largest oil refinery and the crown jewel of Britain’s petroleum empire. Britain’s loss of Abadan sparked what became known as the Abadan Crisis: a confrontation marked by sanctions, a naval blockade, and a global campaign to isolate Iran.

Defending the move before parliament, Mossadegh proclaimed, “This country’s resources belong to its people, not to foreign powers.”

Britain’s loss of Abadan delivered a severe blow to its imperial prestige and economic interests. As the crisis deepened, London escalated its response—pushing beyond economic sanctions and the naval blockade to covert measures aimed at toppling Mossadegh.

These early efforts, from backing rival political factions to stirring street unrest, faltered in the face of his enduring popularity, rooted in decades of public trust and a reputation for integrity and service.

Meanwhile, the United States initially watched cautiously. The Truman administration recognized the strategic importance of Iran’s oil but was reluctant to intervene directly. By 1952, with the Eisenhower administration poised for a more aggressive stance, American policymakers increasingly viewed Mossadegh through the prism of Cold War anxiety. British intelligence pressed the U.S. to act decisively, citing both economic and strategic imperatives.

Domestic politics further complicated the picture. Mossadegh’s broad popular support coexisted with internal divisions: monarchists loyal to the Shah—a secular elite with competing ambitions—as well as religious figures whose support could sway public sentiment.

The Tudeh Party, while significant, was never the principal threat Mossadegh’s opponents claimed, instead serving as a convenient pretext for framing oil nationalization as a step toward communist infiltration.

By early 1953, the stage was set for a decisive confrontation. British and American intelligence agencies coordinated a covert strategy to remove Mossadegh—Operation AJAX (TPAJAX). Far from a spontaneous uprising, the coup relied on carefully devised appearances of popular dissent to achieve its objectives.

Mossadegh’s rise, the nationalization of oil, and mounting foreign intervention created a volatile landscape in which Iran’s sovereignty and democracy faced unprecedented external and internal pressures.

Operation AJAX/Boot: Planning & Strategy

The opening months of 1953 saw the drive to remove Mohammad Mossadegh shift from mere discussion to execution. Britain, having exhausted economic and diplomatic avenues, leaned on the United States to intervene decisively.

The Eisenhower administration, prioritizing Cold War containment and strategic access to oil, empowered the CIA to orchestrate a covert operation in Iran. Britain initiated Operation Boot, and the CIA joined under the code name TPAJAX.

The coup was spearheaded by Kermit Roosevelt Jr., acting on behalf of the CIA in Iran, and Norman Darbyshire of MI6. Their mission: to undermine a widely supported government while avoiding open confrontation and keeping the population sufficiently pacified. Achieving this required a complex web of coordinated, interlocking strategies.

Mechanisms of Regime Change

The removal of Mohammad Mossadegh was meticulously schemed through a calculated fusion of political bribery, psychological warfare, street-level manipulation, and the legitimizing imprimatur of the monarchy.

CIA and MI6 operatives discreetly funneled substantial funds to key military officers and parliamentarians, securing their loyalty and ensuring the fracture of institutional allegiance. Compounding this, Mossadegh’s growing centralization of power had alienated certain segments of the clergy, undermining his broader domestic support.

Together, these pressures systematically eroded his political standing, creating precisely the vulnerabilities that the foreign-backed plot ultimately exploited.

At the same time, a painstakingly calculated propaganda offensive swept through newspapers and radio broadcasts, disseminating forged royal decrees and precautionary announcements of Mossadegh’s resignation, crafting the illusion of governmental collapse and inflaming fears of communist infiltration and economic disaster.

On Tehran’s streets, paid mobs and hired instigators clashed with Mossadegh’s supporters, their carefully staged skirmishes presented as spontaneous uprisings—a contrived spectacle designed to portray him as having lost command of the nation.

Adding to the pressure, the Shah—although initially hesitant—was compelled to sign decrees dismissing Mossadegh, enabling the coup’s architects to cloak their intervention in the veneer of internal legitimacy. What appeared as a constitutional and monarchical resolution masked the decisive hand of foreign planners, preserving the illusion of sovereignty while marshaling a profound political upheaval.

This intricate, multi-layered strategy revealed a sophisticated grasp of Iran’s volatile political terrain. Mossadegh’s deep-rooted popular support rendered a direct military seizure untenable, necessitating the fabrication of widespread dissent, the deployment of psychological manipulation, and the precise positioning of loyalist forces to fracture the government from within.

Operation AJAX and Boot exemplified the power of covert intervention to dismantle a leader who dared confront entrenched global interests, reshaping a nation’s political destiny under the guise of stability and anti-communist vigilance, leaving a legacy of subverted democracy and enduring geopolitical consequences.

The Blow-by-Blow of August 1953

August 15: Final Preparations and Rising Tensions

Roosevelt and his team executed the final preparations for the opening phase of Operation AJAX. Vast sums of cash flowed into the hands of pliant military officers and parliamentarians, while British intelligence cultivated alliances with tribal leaders, painting Mossadegh’s nationalist policies as existential threats to the nation’s stability.

Propaganda surged across media channels, depicting him as a force of chaos, a leader driving Iran toward disorder and collapse.

Undeterred, Mossadegh addressed the nation, appealing to the deep currents of Iranian nationalism and the enduring principles of constitutional democracy.

He navigated a treacherous domestic landscape—juggling competing political factions, societal tensions, and the looming shadow of foreign intervention—while standing firm against British sanctions and the tightening grip of a naval blockade.

August 16: Initial Attempt and Temporary Failure

The opening phase of the operation—anchored in the mobilization of malleable military officers and staged street demonstrations—collapsed almost immediately. The Shah’s hesitation to fully commit sowed confusion among the collaborators, while clashes between paid agitators and Mossadegh’s supporters failed to tip the scales in favor of the conspirators.

Loyalist forces swiftly reasserted control over critical positions, demonstrating not only the resilience of Mossadegh’s popular base but also the convoluted and unpredictable nature of Iran’s political landscape. The early failure exposed the limits of foreign maneuvering in the face of a leader whose legitimacy resonated deeply with his people.

August 17–18: Recalibration and Intensified Propaganda

The CIA and MI6 intensified their efforts, broadening networks of paid agitators while inundating Tehran’s media with fabricated reports and misleading narratives.

The Shah’s temporary departure from the capital heightened the sense of a power vacuum, fueling uncertainty and alarm throughout the city. Carefully nurtured rumors of widespread unrest were deployed to undermine confidence across all layers of Iranian society, making the government appear fragile and disoriented.

August 19: Final Push and Coup Success

Violent street clashes erupted across Tehran as military units loyal to the coup seized key government buildings and communications centers.

Roosevelt documented the decisive moment: “Royalist troops advanced under cover of chaos. The Shah signed the decree dismissing Mossadegh, which was immediately broadcast to the nation.”

By afternoon, Mossadegh had been arrested. His residence was ransacked and set ablaze, while his supporters faced imprisonment, torture, or execution. Western-backed authorities swiftly annulled the nationalization of Iranian oil, restoring foreign control and cementing Western dominance over the country’s strategic resources.

Politically, the coup solidified the Shah’s unchallenged authority, curtailed civil liberties, and inaugurated decades of authoritarian rule enforced through SAVAK.

Operation AJAX would henceforth stand as a standard for future U.S.-led covert interventions, illustrating how foreign powers could systematically undermine democratic institutions under the guise of safeguarding stability, combating communism, or protecting so-called national interests.

Aftermath & Consequences

The overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh in August 1953 was far more than the removal of a prime minister—it marked a defining inflection point in Iran’s political and social trajectory, with aftershocks across the Middle East and the wider world.

The immediate shockwaves and enduring aftermath restructured Iran’s governance and its relations with the West, laying the groundwork for Cold War-era interventionist strategies.

Consolidation of the Shah’s Power

Following Mossadegh’s arrest, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was restored to full authority, presiding over a monarchy that increasingly veered toward autocracy. Western political and financial backing emboldened the Shah, enabling the systematic dismantling of independent political parties, the suppression of press freedoms, and the silencing of dissent through intimidation and violence.

SAVAK, the Shah’s intelligence apparatus, became the central instrument of control, employing surveillance, coercion, and torture to eliminate opposition. Constitutional monarchy effectively gave way to centralized authoritarianism, hollowing out parliamentary oversight and civic participation.

Reversal of Oil Nationalization

Mossadegh’s crowning achievement—the nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC)—was swiftly undone. The 1954 consortium agreement restored foreign control over Iran’s oil, granting British and American firms substantial shares.

This reversal undermined the economic sovereignty that had galvanized national support for Mossadegh, revealing the strategic priority Western powers placed on resource control over self-determination.

Impact on Iranian Society and National Consciousness

The coup inflicted profound psychological and political trauma across Iranian society. For many, the violent removal of a democratically elected leader by foreign powers symbolized the betrayal of both democracy and national dignity.

While Mossadegh’s era did not directly give rise to the Islamic Revolution of 1979, his tenure remains a defining episode in Iran’s modern political history. The 1953 coup illustrated both the vulnerabilities of national sovereignty in the face of foreign intervention and the challenges of navigating domestic politics as a secular nationalist leader.

Mossadegh’s struggle over Iran’s oil, his commitment to constitutional governance, and the popular mobilization around his policies left an enduring imprint on the nation’s political consciousness, shaping the ways Iranians viewed external powers, civic engagement, and the stakes of self-determination—lessons that resounded long after his removal.

The Broader Middle Eastern Context

The repercussions of 1953 exposed the fragility of states attempting to assert independence over strategic resources, setting a pattern repeated in diverse forms—from coups to proxy conflicts—throughout the region.

Mossadegh’s removal became a precedent in the global playbook of imperial power, demonstrating how external forces could orchestrate domestic upheaval under the guise of legitimacy, leaving consequences that continue to shape political realities to this day.

Declassified Insights & Iranian Perspectives

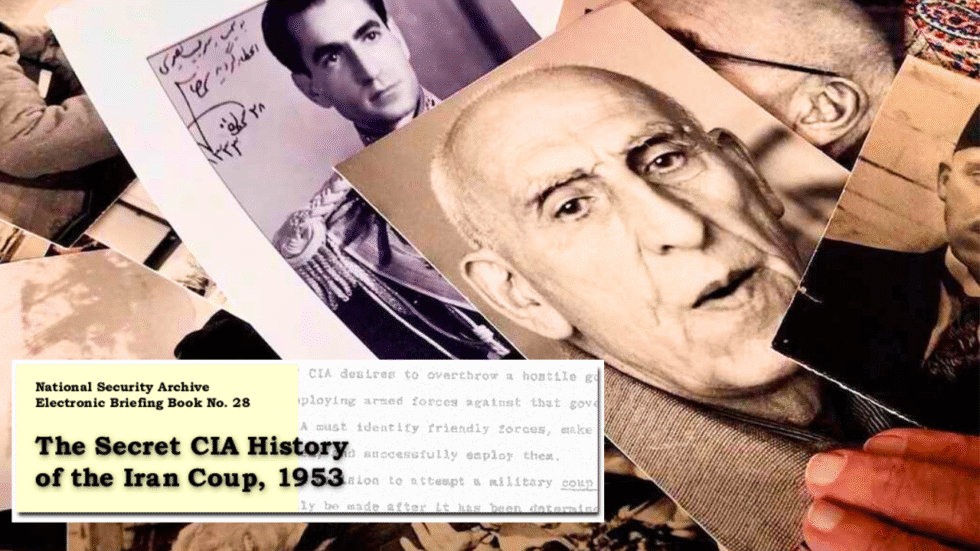

Decades after the coup, the gradual release of declassified documents and memoirs illuminated the vast scale and meticulous planning behind Mossadegh’s removal.

These sources, coupled with Iranian firsthand accounts, reveal an operation engineered to appear internally driven while being decisively directed from abroad—an illusion that deepened the sense of national betrayal.

CIA and MI6 Records: Acknowledging Direct Involvement

Internal CIA histories, declassified in the 1970s and 2000s, openly acknowledge the agency’s decisive role in Operation AJAX.

A 1976 CIA internal history describes the operation as “a decisive intervention to protect Western interests in the region, involving covert funding, manipulation of political and religious figures, and orchestrated public demonstrations” [CIA, The Battle for Iran, 1976].

British archives similarly confirm MI6’s pivotal role, depicting the nationalization of Iranian oil not merely as an economic challenge but as a direct threat to Britain’s strategic influence.

A 1952 memorandum bluntly stated: “Removing Mossadegh is essential to protect our oil interests and maintain geopolitical advantage” [UK National Archives, MI6 Records on Iran, 1953]

Street-Level Manipulation and Media Control

Records show that the coup’s success hinged on shaping both the streets and the public narrative. Paid mobs clashed with Mossadegh’s supporters, while manipulated media—through newspapers and radio—pre-emptively announced his dismissal, exaggerated discontent, and spread disinformation. This coordinated psychological warfare eroded confidence in his leadership and paved the way for the Shah’s restoration.

Iranian Accounts: Shock, Betrayal, and Resistance

For many Iranians, the coup was a shock of historic proportions. Memoirs, interviews, and parliamentary records convey disbelief that a democratically elected leader could be toppled through foreign machinations.

Hossein Fatemi, Mossadegh’s foreign minister, expressed this sentiment before his execution in 1954: “We fought for our country’s freedom, yet were undone by foreign hands wielding money and deceit”

[Interview, The Iranian Revolution and Its Aftermath, 1980]

Oral histories recall Tehran’s streets engulfed in chaos, with ordinary citizens caught between rival factions manipulated by outside actors.

Scholarly Analysis and Contemporary Understanding

Historians such as Ervand Abrahamian and Mark Gasiorowski contend that the coup was less about combating communism than preserving imperial control and economic interests.

Abrahamian notes: “The overthrow of Mossadegh is not merely a chapter in Iranian history; it is a foundational event defining Iran’s complex, often antagonistic relationship with the West”

– Abrahamian, The Coup: 1953, CIA and Modern U.S.-Iranian Relations, 2013

Patterns of Imperial Intervention

This historical event in Iran stands as a seminal example of a persistent and global pattern of imperial interventionism, in which the United States, often in close coordination with allied powers, systematically destabilized or removed elected leaders who sought to assert control over national resources or political autonomy.

Mossadegh’s assertion of Iranian independence directly challenged entrenched foreign dominance and established a template for covert operations disguised as guardians of democracy—a pattern repeated with unsettling consistency in decades that followed.

Latin America: Guatemala and Chile

This pattern swiftly extended across continents. In Guatemala, the 1954 CIA-backed coup dismantled the government of President Jacobo Árbenz, whose ambitious land reforms threatened the holdings of the U.S.-based United Fruit Company. Justified publicly under the banner of anti-communism, the intervention secured the continuity of external control over Guatemalan agriculture and reinforced U.S. influence in Central America.

Similarly, Chile’s socialist government under Salvador Allende faced persistent covert sabotage and the systematic funding of opposition forces, culminating in a military coup that installed Augusto Pinochet.

Anti-communism was the stated rationale, yet the underlying objective was unmistakable: to guarantee Western access to critical resources and enforce political compliance through strategic, often violent, manipulation.

Africa and Southeast Asia: Congo, Indonesia and Libya

Comparable intrusions unfolded in Africa and Southeast Asia, illustrating the global reach of these interventionist strategies. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba’s efforts to assert national control over mineral wealth provoked orchestrated action by U.S. and Belgian actors, culminating in his execution.

In Indonesia, President Sukarno was methodically undermined by U.S.-backed military factions in 1965, leading to mass killings and the installation of Suharto’s authoritarian regime.

Even decades later, in Libya, foreign-backed regime change in 2011—framed as civilian protection—left the nation fractured under competing armed groups, echoing the destabilization first witnessed in Iran.

Syria: The Modern Reflection of Intervention

Syria, in recent years, has come to embody the persistent legacy of this pattern.

In December 2024, President Bashar al-Assad—who had maintained a secular government committed to safeguarding Syrian sovereignty under immense regional and Western pressure—was forcibly removed from power. Violent militants, led by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) under Ahmad al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Muhammad al-Julani, seized control of Damascus, driving Assad into exile in Russia.

The irony is stark: al-Julani, once denounced by Western powers as a terrorist, had been strategically cultivated and manipulated as an instrument of regime change, demonstrating the calculated exploitation of local actors to advance foreign objectives.

In the wake of Assad’s ouster, HTS installed a transitional government under interim president al-Julani. Yet the nascent administration struggled to assert authority or maintain order.

By mid-2025, escalating sectarian violence between Druze militias and Sunni Bedouin factions had exacted a devastating toll—thousands killed, entire communities uprooted, and hundreds of thousands displaced amid an intensifying humanitarian catastrophe.

The resulting turmoil underscores, with brutal clarity, the human cost of foreign intervention, particularly when local proxies are empowered in the absence of genuine governance structures or institutional legitimacy.

The Paradox of Rhetoric Versus Reality

Across Iran, Guatemala, Chile, Congo, Indonesia, Libya, and Syria, a common paradox emerges: the rhetoric of democracy, stability, and human rights frequently belied the reality of resource extraction, geopolitical manipulation, and strategic domination.

Nations striving for independence and control over their resources repeatedly confronted covert warfare, propaganda, economic sabotage, and orchestrated coups, all concocted from abroad.

Mossadegh’s overthrow, in this broader context, is not an isolated incident but the opening chapter in a global saga of interventionism whose consequences ring across generations.

The strategic calculus remains consistent: imperial powers advance their interests under the guise of benevolence, often at profound human cost, systematically undermining political autonomy and long-term stability in the nations they target.

The Precedent of Defiance

The overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh was never merely the removal of a leader; it was a global message delivered in the language of power: sovereignty carries a price, and those who insist upon it risk the full machinery of empire.

Mossadegh’s audacity—to nationalize Iran’s oil, to reclaim control over the nation’s wealth, to confront entrenched Western interests—was met with clandestine violence, subterfuge, and betrayal.

1953 did not stumble into history; it carved a template for empire in motion. The orchestration of coups, the use of proxies, the manipulation of domestic factions, and the justification of intervention under the guise of democracy became a blueprint repeated across continents and decades.

Iran experienced this lesson in the most visceral terms: external powers respect only compliance, not conscience; profit, not principle.

The ripples of this historical event continue to shape Iranian policy and national psychology. From the Cold War to sanctions, from covert operations to diplomatic isolation, the memory of Mossadegh’s overthrow informs every calculation.

Iran’s modern posture—skeptical of Western promises, vigilant against foreign interference, unyielding in defense of national assets—is rooted not in ideology alone but in the scars carved by decades of foreign ambition and the betrayals of manipulated allies.

Yet the shadow of 1953 is not only one of subjugation; it is also a testament to resilience. The lesson was brutal but unequivocal: freedom is fragile, and sovereignty is never given. It must be claimed, defended, and defended again.

Iran’s repeated confrontations with the entrenched machinery of foreign intervention—in diplomacy, finance, and covert operations—have shaped a nation that remains steadfast, alert, and unwilling to compromise to this day.

Seventy-two years on, the shadow of the coup still looms. Tehran bears the memory, while Washington, London, and every capital that once believed it could bend Iran to its will now reckon with a nation that refuses to yield. The lessons of this historic episode resonate in Iran’s politics, its posture, and its people.

A nation’s sovereignty, once trampled, does not vanish. It strikes, it survives, and it declares that those carved by empire will never forfeit their dignity without defiance.

References

- Mossadegh.com. (n.d.). Biography of Mohammad Mossadegh. Retrieved from http://www.mossadegh.com/biography

- Encyclopedia Britannica. (2023). 1953 coup in Iran. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/1953-coup-in-Iran

- History.com Editors. (2022). CIA-assisted coup overthrows government of Iran. History.com. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/cia-assisted-coup-overthrows-government-of-iran

- CIA Reading Room. (1953). The Central Intelligence Agency and the Fall of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/the%20central%20intelligence%20%5B15369853%5D.pdf

- The National Security Archive. (2013). CIA Confirms Role in 1953 Iran Coup. Retrieved from https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB435/

- History Today. (2015). Iran, Britain and Operation Boot. Retrieved from https://www.historytoday.com/daniel-wb-lomas/iran-britain-and-operation-boot

- PBS LearningMedia. (2020). Operation Ajax: The Plot to Overthrow Iranian Prime Minister Mossadegh. Retrieved from https://klrn.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/amex34th-soc-operationajax/operation-ajax-the-plot-to-overthrow-iranian-prime-minister-mossadegh-taken-hostage/

- The Guardian. (2023). ‘Written out of the history books’: the British spy who planned the Iranian coup. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/15/written-out-the-history-books-the-british-spy-who-planned-the-iranian-coup

- The Washington Post. (2025). The U.S. helped oust Iran’s government in 1953. Here’s what happened. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2025/06/19/iran-coup-1953-us-role/

- CIA. (1976). The Battle for Iran: Internal CIA History on Operation AJAX. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80R01723R000100120007-7.pdf

- UK National Archives. (1953). MI6 Records on Iran: Operation Boot and the Overthrow of Mossadegh. Kew, London.

- Fatemi, H. (1980). Interview in The Iranian Revolution and Its Aftermath. Tehran: Iranian Oral History Project.

- Abrahamian, E. (2013). The Coup: 1953, CIA and Modern U.S.-Iranian Relations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gasiorowski, M. (1991). U.S. Foreign Policy and the Shah: The 1953 Coup in Iran Reconsidered. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 23(3), 361–386.

- Kinzer, S. (2003). All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kinzer, S. (2006). Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. New York: Times Books.

- Gleijeses, P. (1991). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kornbluh, P. (2003). The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability. New York: The New Press.

- Nzongola-Ntalaja, G. (2002). The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila – A People’s History. London: Zed Books.

- Cribb, R. (1990). The Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966: Studies from Java and Bali. Clayton: Monash University Centre of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Vandewalle, D. (2012). A History of Modern Libya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Phillips, C. (2016). The Battle for Syria: International Rivalry in the New Middle East. New Haven: Yale University Press.

If you value our journalism…

TMJ News is committed to remaining an independent, reader-funded news platform. A small donation from our valuable readers like you keeps us running so that we can keep our reporting open to all! We’ve launched a fundraising campaign to raise the $10,000 we need to meet our publishing costs this year, and it’d mean the world to us if you’d make a monthly or one-time donation to help. If you value what we publish and agree that our world needs alternative voices like ours in the media, please give what you can today.